Dr. Volkmar Denner

chairman of the board of management, Robert Bosch GmbH,

at the ceremony to open the Dresden wafer fab

on June 7, 2021

Minister-President Kretschmer,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

The opening of this new wafer fab here in Dresden is an event we cannot really celebrate in the usual sense. Our pleasure is unfortunately only virtual, as the pandemic is still with us. And even if we leave Covid-19 aside, the challenges policymakers and businesspeople face could scarcely be more daunting: climate action, digitalization, and not least Europe’s technological sovereignty are the order of the day. All these things call for a response from industry as well. And it is precisely the tiniest electronic components than can help us rise to the greatest challenges. For me, therefore, it is absolutely clear that nothing is more appropriate to this present age and its huge tasks that a new factory for small things.

No matter when it happens, the opening of a new manufacturing site is always a positive signal – for a company’s investment clout, for nationwide employment, and finally for the future of all involved. But there is even more at stake here, as the supply shortages in the semiconductor industry already show. This is about the resilience of global supply chains – and also about the stance European industry should take. While it doesn’t need to strive for self-sufficiency, neither must it be dependent on the economic and technological strength of other global regions. So while I’m not saying that this new wafer fab will solve this problem on its own, it can certainly be part of the solution.

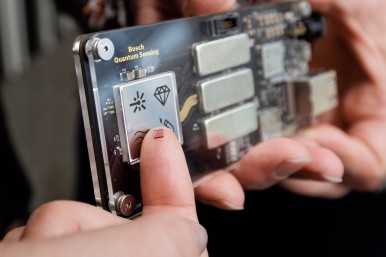

Any innovations the future brings will also need microelectronics. Without it, there can be no artificial intelligence, making things such as automated driving possible. Without it, there can be no quantum sensor technology, making the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s easier and more precise in the future. And without it, there can be no sustainable mobility. Take the silicon-carbide chips Bosch uses in its power electronics. They extend the range of electric vehicles. Semiconductors that are secure and reliable, and that also control and regulate complex environments – that is what all present and future applications need. The impact of this new plant will be felt far beyond our company, and far beyond Dresden. This is where technology for tomorrow’s world will be created.

We are glad that the EU Commission, the federal government, and the state government appreciate the strategic significance of microelectronics – and are acting in concert. This joint support is expressed in the synonym IPCEI, which stands for “important project of common

European interest.” This is a special subsidy program that had its premiere in the microelectronics industry. It is also thanks to this program that Bosch was able to build this wafer fab in Dresden. At roughly one billion euros, this is the biggest single investment in the history of our company.

The building itself was successfully completed within a short timeframe. For that, I would like to thank all involved – our Bosch associates, the construction companies, and the suppliers and installers of the machinery. You could say that it all went to plan in conditions nobody had planned for. In fact, we have begun to roll out production six months earlier than planned. In view of the current supply shortages in the semiconductor industry, this is a team effort that cannot be praised highly enough. But how was this possible? Not least thanks to remote collaboration with the help of 3D data glasses, which kept our installers on site connected with suppliers around the world, as they worked on setting up the machinery. There could scarcely be a better illustration of how valuable digital work is in times of coronavirus – and this too is something that would not work without microelectronics.

3D data glasses, 5G connectivity, the use of artificial intelligence to evaluate machine and product data – all these things will be typical of the high-tech working day in our new wafer fab. This is the first ever Bosch manufacturing facility to be organized from top to bottom as an AIoT factory. AIoT is the combination of artificial intelligence and the internet of things. It is the source of a new kind of efficient production: AI algorithms can detect process anomalies in the countless millions of data generated every day, and optimize the complex sequence of up to 700 process steps that each wafer goes through. And most importantly, in my view, using the methods of artificial intelligence in our fully connected factory allows us to secure a high level of process stability in a short time. This saves our automotive customers the need for the time-consuming trials that would otherwise be necessary before production release. So we can not only produce earlier, but deliver reliable products earlier as well.

Here in Dresden, therefore, the future is on view – the vigor of a plant that will be an AIoT factory from the get-go. It is a factory that also brings additional strength to a microelectronic ecosystem that is already unrivalled – Silicon Saxony. I am confident that both our new location and the region as a whole will share in the growth of the German and European semiconductor industry. Of course, this industry will have to hold its own in a global environment that remains challenging. It has got what it takes to do so, provided the right decisions are made. It’s good that there will be a second microelectronics IPCEI – the process has already got underway at EU level, and the federal government has signaled its support. It remains for me to hope that the new program will quickly be put into practice. But when it comes down to it, what is it that really matters? The European semiconductor industry has to preserve its innovative strength in international competition. Above all, it will manage this by combining systems and chip expertise. In other words, it’s not just finer chip structures that are important, but also the future generations of power electronics and micromechanical sensors – and not least, new applications such as quantum sensor technology.

The new factory will prove its worth in the global competition for innovation. For Bosch, it is already part of a global engineering and manufacturing network. All the better that the factory’s associates come from 24 countries. And while Bosch may be a company with southwest German roots, it is now more strongly rooted in Saxony as well. But what is the best thing about globalization? It’s that a company like Bosch can bring together people from different cultures. This is also something that can be experienced in our new factory. We wish everyone who works here every success, combined with our sincere thanks to all those who have worked so hard to make this venture possible.