What refrigerators have to do with heat-pump development

In 1852, William Thomson published a paper on refrigerators that worked on the principle of compression. In reverse, he suggested, they would also be excellent for heating. In his research on “heating machines,” Thomson showed that they would require much less primary energy than conventional direct heating. Peter Ritter von Rittinger is regarded as the inventor of the first heat pump: a system for evaporating brine that he presented in 1853. The process yielded an energy saving of 80 percent compared to the conventional evaporation process using wood. In other words, the contemporary scarcity of wood was the trigger for the development of this pioneering patent.

However, heat pumps did not gain acceptance until the 20th century, with fuel shortages in various decades playing a major role. Particularly in the United States, which was largely spared the effects of the first world war, air conditioners were already being built with a heating function as standard in the 1920s. In Zurich, Switzerland, the city hall was equipped with a substantial heat-pump system for heating in 1938. The first ground-coupled model then appeared in the U.S. in 1945.

1975: Bosch presents first-generation heat pump and starts production

Under the Junkers brand, the first Bosch heat pump was installed as a prototype in a residential building in Wernau am Neckar, Germany, in January 1975. It used well water as its heat source. Heat pumps went into production in the same year. The smaller, improved second-generation heat pump went into production in 1982.

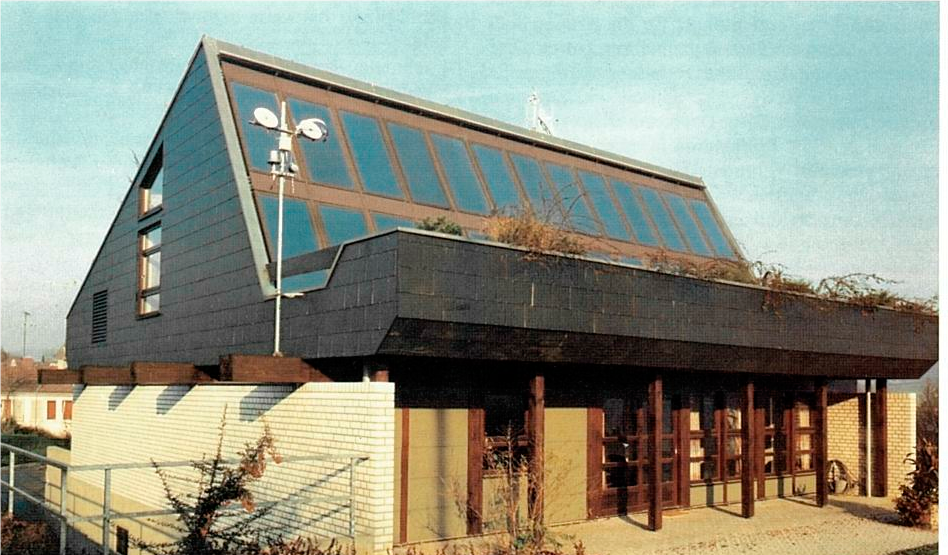

The oil crisis in the 1970s drives development forward

The “Tritherm” house was a single-family home built as a pioneering prototype in 1976 on the factory premises of Junkers, then a division of Bosch, in Wernau. As its name suggests, the house made use of three heat sources. Starting in 1977, research was conducted here on ways of saving energy and resources. The oil crisis drove home the finite nature of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas. This realization prompted researchers in many fields – not just in heating technology – to search for alternative sources of energy that would help conserve resources. The building’s 174 square meters of living space, complete with basement and 1,400 cubic meters of enclosed space, featured groundbreaking technology: heating and hot water were provided by a heat pump with an air-to-air heat exchanger, which extracted heat from the outside air, together with 25 solar collectors covering an area of some 40 square meters. Solely as a reserve for peak loads on the coldest winter days, there was also a conventional central heating system using liquefied petroleum gas. The results were impressive even then: these systems lowered the fuel consumption to less than 10 percent of its previous level.

1980: Bosch presents a hot water heat pump

At the Intherm trade fair in Stuttgart, the Junkers brand showcased a new hot water heat pump that could heat tap water to around 50 degrees Celsius. The pump’s performance and capacity were designed for a six-person household.

2004: Bosch acquires the Swedish heat-pump manufacturer IVT

In 2004, Bosch acquired “Industriell Värme Teknik” in Tranås, Sweden, a company set up in 1968. Its core competence was brine-to-water heat pumps, which extract energy from a great depth via a borehole in the ground. This extremely efficient technology, which is still the standard in Sweden today, gained acceptance thanks to a number of major projects in the 1990s – among them the installation of brine-to-water heat pumps at Drottningholm Palace, the summer residence of the Swedish royal family.

2007: Bosch acquires U.S. heat-pump manufacturer FHP

With the acquisition of FHP Manufacturing Company, Fort Lauderdale, Bosch entered the attractive U.S. market for geothermal electric heat pumps, and continued its growth course in the promising renewables segment.

2011: Energy Plus house with heat pump

At the end of 2011, Bosch’s Buderus brand and SchwörerHaus completed a single-family house in Wetzlar that provides more primary energy over the year than its occupants require. This house showed that it was possible to use the available technology to build a house that produces an energy surplus. The first step is to keep energy consumption low by optimizing the building envelope and harnessing residual energy flows. Next, the remaining energy demand must be met as efficiently as possible and the building itself must generate as much electricity as possible. To meet these requirements, the “Energy Plus” house is equipped with a Buderus-brand electric heat pump, with roof-mounted photovoltaic modules, with solar-active low-temperature collectors on the facade, and with a controlled domestic ventilation system featuring heat recovery. Bosch low-consumption home appliances round off the range of domestic equipment. Calculated over the year, this results in a positive energy balance: the expected annual energy demand for home appliances, domestic hot water, ventilation, and heating is 7,550 kWh, while the expected annual electricity generation amounts to 9,100 kWh.

Since 2015: Emissions reductions focus on the building sector

Ever since the 2015 Paris Agreement, the importance of the building sector in achieving climate goals has come into sharper focus. The EU’s stock of existing buildings accounts for some 36 percent of its greenhouse gas emissions1). Achieving climate targets calls for a climate-neutral building stock. The preferred technologies are heat pumps for newly built and refurbished existing buildings, and heat-pump hybrids for unrefurbished buildings. Demand for heat pumps as an environmentally friendly heating solution grew steadily since the late 2010s.

2023: Bosch presents first propane-operated air-to-water heat pump

The latest generation of Bosch heat pumps run on the natural refrigerant propane. Not only does this naturally occurring gas have a low global warming potential, but its ideal thermodynamic properties enable the heat pump to achieve particularly high energy efficiency and higher flow temperatures. Using propane as a refrigerant in heat pumps ensures a futureproof and sustainable supply of heat. The latest-generation heat pumps can also be installed together with a conventional heat generator in a combination known as a heat-pump hybrid. This is a fast and cost-effective way of switching unrefurbished existing buildings to alternative heating. In both day and night modes, the latest-generation heat pumps are characterized by low noise levels. This makes them suitable for use in densely built-up terraced housing estates.

1) https://commission.europa.eu/news/focus-energy-efficiency-buildings-2020-02-17_en